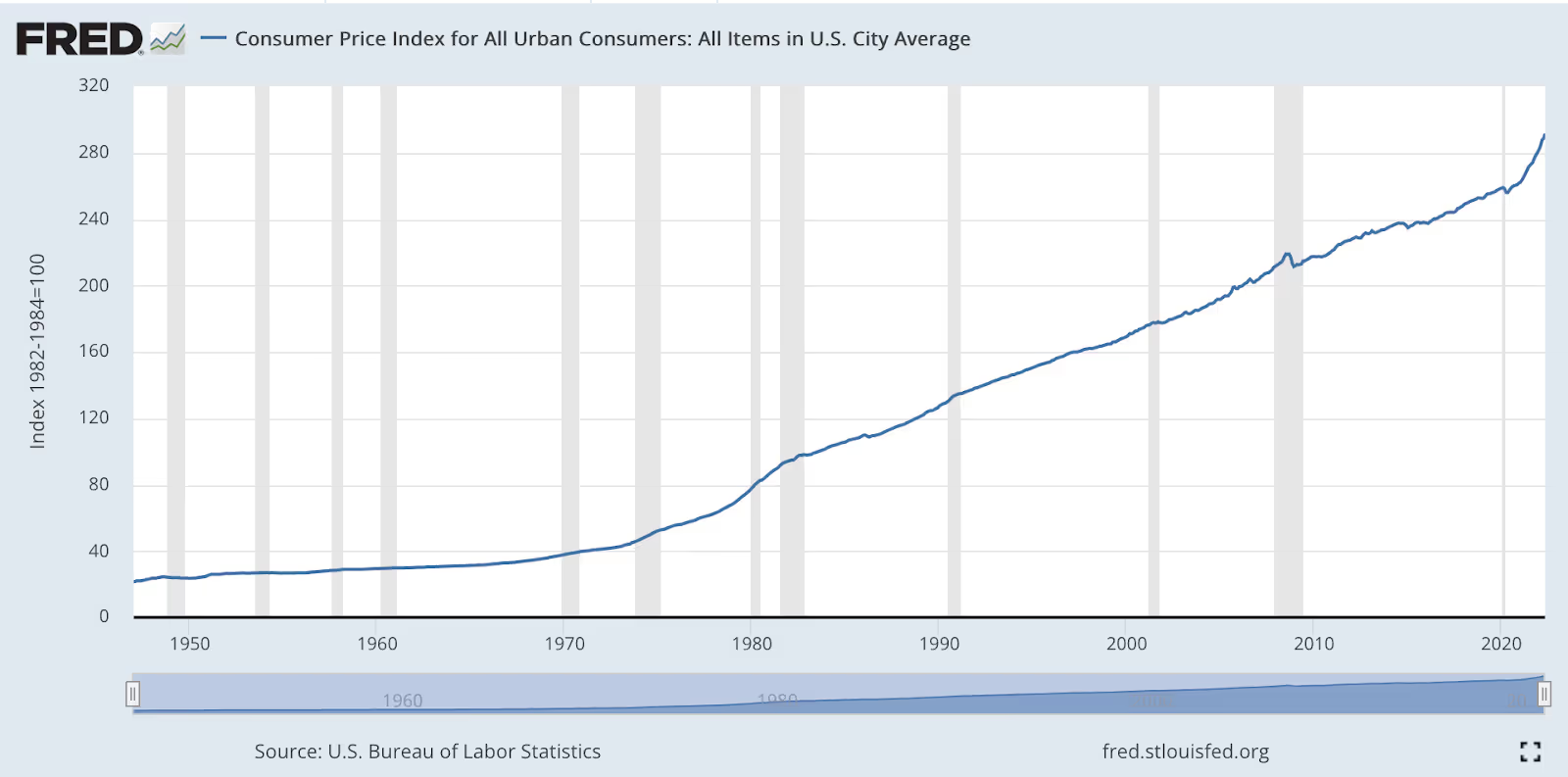

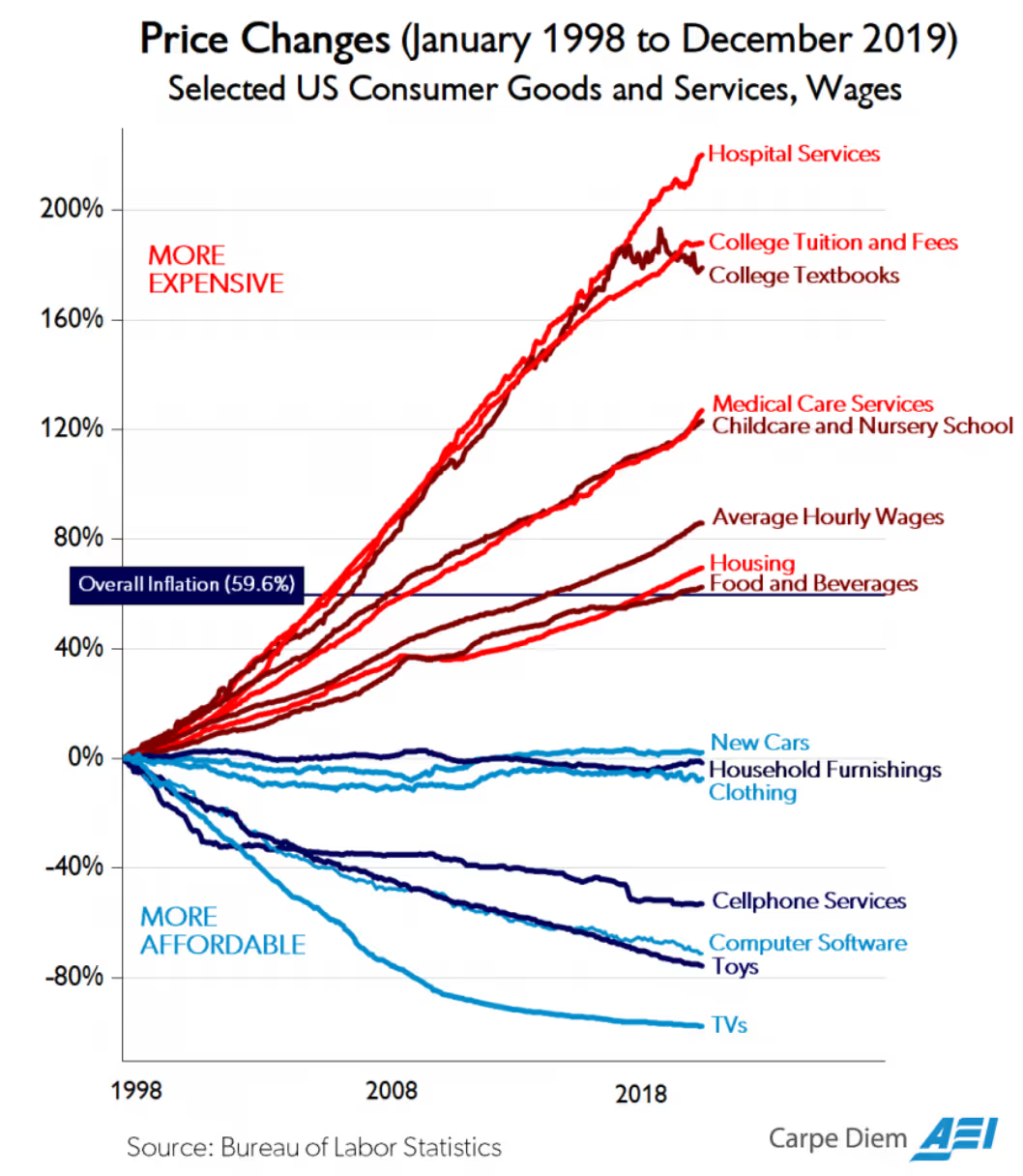

We take for granted that prices rise over time. As shown in Figure 1, the consumer price index for items in American cities has increased dramatically since the 1940s. To be sure, once one adjusts for inflation, some real prices have fallen over time. As shown in Figure 2–the so-called “Chart of the Century”-goods such as new cars, household furnishings, clothing, and cellphones have all become more affordable.

Figure 1: Consumer Price Index for U.S. City Residents, 1947-2022 (Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics)

Figure 2: Prices Changes Relative to Inflation, United States, 1998 to 2019 (Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics)

A real price is one that is adjusted for inflation. For example, if the price of a car doubles in a given year, but inflation is such that wages have risen threefold, then the real price of a car has fallen.

But why is adjusting for inflation necessary in the first place? Although we’re used to having to do this, it should strike you as an odd, almost ad hoc bit of extra work. Wouldn’t life be easier if we could just observe unmodified prices and measure them over time?

Adjusting for inflation is necessary whenever a society is using a money whose supply grows over time.

The change in price of any good is determined by two counterveiling forces: innovation and growth in the money supply.

Innovation pressures prices to fall in a few ways. For example, an entrepreneur might discover a more cost-effective method by which to produce a good that has already been on the market. He can then afford to sell the good more cheaply than his incumbent competitors. Assuming this innovator takes a significant portion of the market, customers now enjoy this good at a lower price than they did. For example, Walmart came to prominence by offering everyday products at a lower price than the incumbents, resulting in cheaper goods for all consumers.

An entrepreneur may also discover a novel way by which to expand the supply of some good. Fundamental economics tells us that whenever the supply of a good increases, the price per unit good must fall (all else being equal). As has happened in the energy sector in the United States, new ways of acquiring energy sources has led to a fall in energy’s real price over time.

The force that works against innovation and drives prices upward is expansion of the money supply. As I mentioned earlier, when the supply of a good increases, its unit price falls. The same is true for money, except that the ‘price’ of a dollar is the amount of goods one can trade for said dollar. So, if the supply of money increases, then each dollar buys fewer goods than it did before the supply increase.

Intuitively, innovation benefits most of humanity. Cheaper, higher-quality goods make life more prosperous, and greater abundance makes previously expensive items affordable by more and more people. Granted, those entrepreneurs who lose in the market (such as the Mom-and-Pop shops who lose business to Walmart) feel like they’ve suffered because of an innovation that drove them out of business. But even they benefit from the wider availability of goods and services. After all, the owners of horse-and-buggie companies could still buy cars–and their descendants enjoy only the benefits of the invention of cars without the drawback of having been run out of business. In short, humanity is made wealthier overall by innovation.

An increasing money supply, on the other hand, benefits the few at the cost of the many. Unlike with innovations, humanity is not made wealthier by an expanding money supply. No new goods have been created, no novel ways of offering services have been discovered, no cost-efficient modes of production have been implemented. Rather, a kind of reverse Robin Hood has taken place: those who acquire the newly created money have siphoned wealth from everyone else.

In our system, this means that central bankers and their allies enjoy an increase in wealth at the cost of regular citizens who are economically distant from them. Those who have access to the new money just after it’s been created are able to buy goods and services before their prices rise in response to the new money supply. Those who acquire the new money much later–typically those on fixed incomes–only do so after goods and services have risen in price. This phenomenon is called the Cantillon effect.

In a world of inflation, the rich get richer while the poor get poorer.

In a world of a fixed money supply, prices don’t have to be adjusted for inflation. Among other things, this means that businesses have to be far more honest with society, as they can no longer hide a lack of productivity behind distorted price signals. There would be no manipulation of cost-of-living data and inflation indices. Agenda-driven bureaucrats could not mask the effects of their schemes.

This isn’t some fantastical thought experiment. On the contrary, Bitcoin is the hardest money ever invented.

If we want a world of falling prices, Bitcoin is the road to get there.